Are Confucius’ words “choose a job you love and you will never have to work a day in your life” inconceivable, or are they wise and applicable for people today?

Are Confucius’ words “choose a job you love and you will never have to work a day in your life” inconceivable, or are they wise and applicable for people today?

This article explores the importance of establishing meaning and flow, while avoiding burnout, if we want to not just survive, but thrive at work and in life.

As an transpersonal coach, I have noticed that a reasonably consistent theme underlies the common issues that my clients bring to coaching. A summary of this theme is the inability to cope with or resolve challenging circumstances, resulting in feelings of overwhelm, helplessness and frustration that can escalate to mental exhaustion, physical fatigue and emotional bankruptcy. This summary is similar to the way burnout is described by Shirom (1989).

Stress and burnout cause dysfunction among individuals and couples, as well as within organisations (cited in Zeidner, 2005), resulting in lower productivity, higher absenteeism, poorer morale and performance issues (cited in Dierendonck, Garssen & Visser, 2005a). Such stress also causes a type of rigidity that can limit awareness and reduce people’s ability to process information (Zeidner, 1998).

Professor Kavita Vedhara (2010) provides scientific evidence for the fact that stress negatively affects the immune system. With burnout being the result of ongoing stress, resulting in fatigue and low energy levels, it stands to reason that a person experiencing burnout will have a higher than normal risk of becoming ill, and once ill, they will experience slower than normal healing from illness. Additionally, the mental exhaustion that is associated with burnout can result in such individuals making poor choices which can perpetuate already problematic situations.

Most existing burnout prevention and treatment programmes have a cognitive-behavioural focus (cited in Dierendonck, et al. 2005b) and therefore don’t address the underlying (unconscious) causes of the issue that they aim to resolve. The roots of burnout stem from multiple levels of causation, of which a vast majority (if not all root causes of burnout) are below the level of conscious awareness among those who are affected by this phenomenon.

People unconsciously prefer vocations that in some way represent their personal and family history. From the psychoanalytic view, we select roles that enable us to replicate emotionally charged and unresolved issues from our early years of life (cited in Pines 2005). Dr. Michel Odent (2010) provides evidence for the fact that our level of mental, emotional and physical health in adulthood is significantly influenced by the attitudes of our mother during our developing months in the womb, as well as by the birth experience itself. Furthermore, burnout is often associated with various emotional and psychosomatic disorders that, according to Dr. Stanislav Grof (2000) develop as a result of the reinforcing influence of traumatic events in our postnatal history, which in turn have causal links to peri-natal, pre-natal and transpersonal origins.

Clearly any effective and sustainable treatment of burnout must take the full spectrum of potential causes into account. A solution-oriented burnout prevention and healing programme which incorporates transpersonal perspectives and practices that are inclusive of all known causal factors is therefore recommended. Such a programme can have far reaching positive benefits for not only organisations and the individuals that work in them, but also for the youth and young adults of today who have to deal with the excessive stressors that have become common to life in our high-tech and low-care society.

Dr. Victor Frankl (1976) considered the desire for meaning to be a core motivation among humans. We experience the flow state known as being in the zone when we are fully engaged with something that we find meaningful. Flow states occur when the energy and resources available to us in the moment are optimal for the activity we’re involved in (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). In this high performance state our awareness becomes focused on the task at hand and our actions are effective, productive and agile. When our flow states are consistently interfered with over time, then our energy begins to deplete, contributing toward burnout. Similarly, being inhibited from pursuing something that we believe to be meaningful, thereby loosing the possibility of achieving a desired goal, is also a significant determinant in the development of burnout (Pines, 1993). Such burnout causing factors are highly prevalent in this day and age. Although being involved in something that we find meaningful may be the perfect antidote to stress and burnout, our fast paced, competitive, economically challenged and technology driven society leaves little room for the pursuit of meaningful occupations and is quick to obscure positive flow states with an abundance of distractions.

Might Transpersonal Psychology and Mindfulness offer a solution?

With insights drawn from cognitive and neuroscientific data, as well as the world’s great spiritual traditions, transpersonal psychology provides a conceptual framework for researching the full spectrum of factors concerning the causes and treatment of burnout. This broad field of psycho/spiritual study offers diagnostic methods, as well as approaches for the prevention and healing of burnout. Being an inclusive psychology that is capable of explaining both mundane and transformative processes of the psyche, transpersonal psychology includes models that are inherently cross-disciplinary and often cross-cultural. This is particularly useful when seeking to unveil the causes and the effects of burnout in a range of contexts.

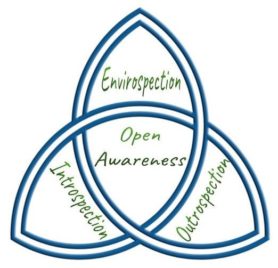

The integration of mindfulness (e.g. applied open awareness) cultivates productive engagement in work, an expanded sense of meaning and purpose, enhanced physical and psychological well-being, and improved relationships (cited in Niemiec, Rashid & Spinella, 2012). The achievement of open awareness may counteract the effects of stressors that can lead to burnout, thus applied open awareness might contribute to the alleviation of burnout symptoms and play a significant role in burnout prevention.

Resent research (Dangeli, 2020) has shown that participants were able to reduce their stress and burnout levels by 58% after 24 days of using applied open awareness. Qualified Open Awareness facilitators are able to assist clients to achieve the insights and healing that are common to transpersonal (non-ordinary) states of consciousness, and in a way that is both achievable and acceptable for the teenager, the teacher, the manager, the executive and the chairman, etc.

We might not all be able to choose a job that we love, but we can all learn how to enjoy our time at work more, while establishing greater levels of meaning and flow in all areas of life, through applied open awareness.

Written by Jevon Dangeli – MSc Transpersonal Psychology, Coach & Trainer

.

References:

Anderson, R and Braud, W. (2011). Transforming others and self through research, New York: State University of New York Press

Csikszentmihalyi, M (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row.

Dängeli, J. (2020). Exploring the phenomenon of open awareness and its effects on stress and burnout. Consciousness, Spirituality & Transpersonal Psychology, 1, 76-91. https://www.journal.aleftrust.org/index.php/cstp/article/view/9

Dierendonck, vD., Garssen, B. and Visser, A. (2005a, 2005b). Rediscovering meaning and purpose at work: the transpersonal psychology background of a burnout prevention programme, in A.G. Antoniou & C.L. Cooper (eds.), Research Companion to Organizational Health Psychology, 40, 623. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited

Frankl, V.E. (1976), Man’s Search for Meaning, New York: Beacon Press.

Grof, S. (2000). Psychology of the future, New York: State University of New York Press, 75

Niemic, R., Rashid, T., Spinella, M. (2012) Strong Mindfulness: INtegrating Mindfulness and Character Strengths. Journal of Mental Health Conseling. Vo. 34. No. 3. 240-253

Odent, M (2010). The Two-Edged Mind: Placebo and Nocebo Responses. The Scientific and Medical Network, audio recording of presentation. Retrieved January 16, 2013, from the World Wide Web: https://www.scimednet.org/assets/Private/Audio/BodyBeyond2010/BB2010Odent.MP3

Pines, A.M. (2005). Unconscious influences on the choice of a career and their relationship to burnout: a psychoanalytic existential approach, in A.G. Antoniou & C.L. Cooper (eds.), Research Companion to Organizational Health Psychology, 38, 580. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limitedfor the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, Loughlinstown House.

Pines, A.M. (1993), Burnout – an existential perspective, in W. Schaufeli, C. Maslach and T. Marek (eds), Professional Burnout: Developments in Theory and Research, Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis, pp. 33–52.

Shirom, A. (1989),‘Burnout in work organizations’, in C.L. Cooper and I. Robertson (eds), International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, New York: Wiley, pp. 26–48.

Vedhara, K (2010). Psychoneuroimmunology: “What has Stress Got to Do with It?”. The Scientific and Medical Network, audio recording of presentation. Retrieved January 14, 2013, from the World Wide Web: http://www.scimednet.org/assets/Private/Audio/BodyBeyond2010/BB2010Vedhara.MP3

Zeidner, M. (2005). Emotional intelligence and coping with occupational stress, in A.G. Antoniou & C.L. Cooper (eds.),Research Companion to Organizational Health Psychology, 16, 218. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited

Zeidner, M. (1998), Test Anxiety: The State of the Art, New York: Plenum.